3 HOW IT ALL BEGAN

MAKING THREE INTO ONE

MAKING THREE INTO ONE

In the 1960s, the idea arose to combine Munich’s three Max Planck Institutes (MPI) in a spacious new building. The goal: to solve the ever-increasing lack of space in the city center and to create synergies. The final decision by the Max Planck Society (MPG) to merge the institutes was made in 1967, and the new large-scale research facility took the name of the largest and oldest of its three predecessors: MPI of Biochemistry. The vision of the project was a polycentric institute, whose departments would develop freely while benefiting from mutual exchange and shared facilities.

No suitable building site was found in Munich itself. Through the mediation of Munich’s mayor Hans-Jochen Vogel, the choice was rural Martinsried (municipality of Planegg), located in the southwest just outside of Munich. There, the MPG acquired a 37-hectare undeveloped site. A particular advantage of the new location was the close proximity to the site where the University Hospital Großhadern was to be built — with the hope for a fruitful cooperation.

FUNCTIONAL ARCHITECTURE

FUNCTIONAL ARCHITECTURE

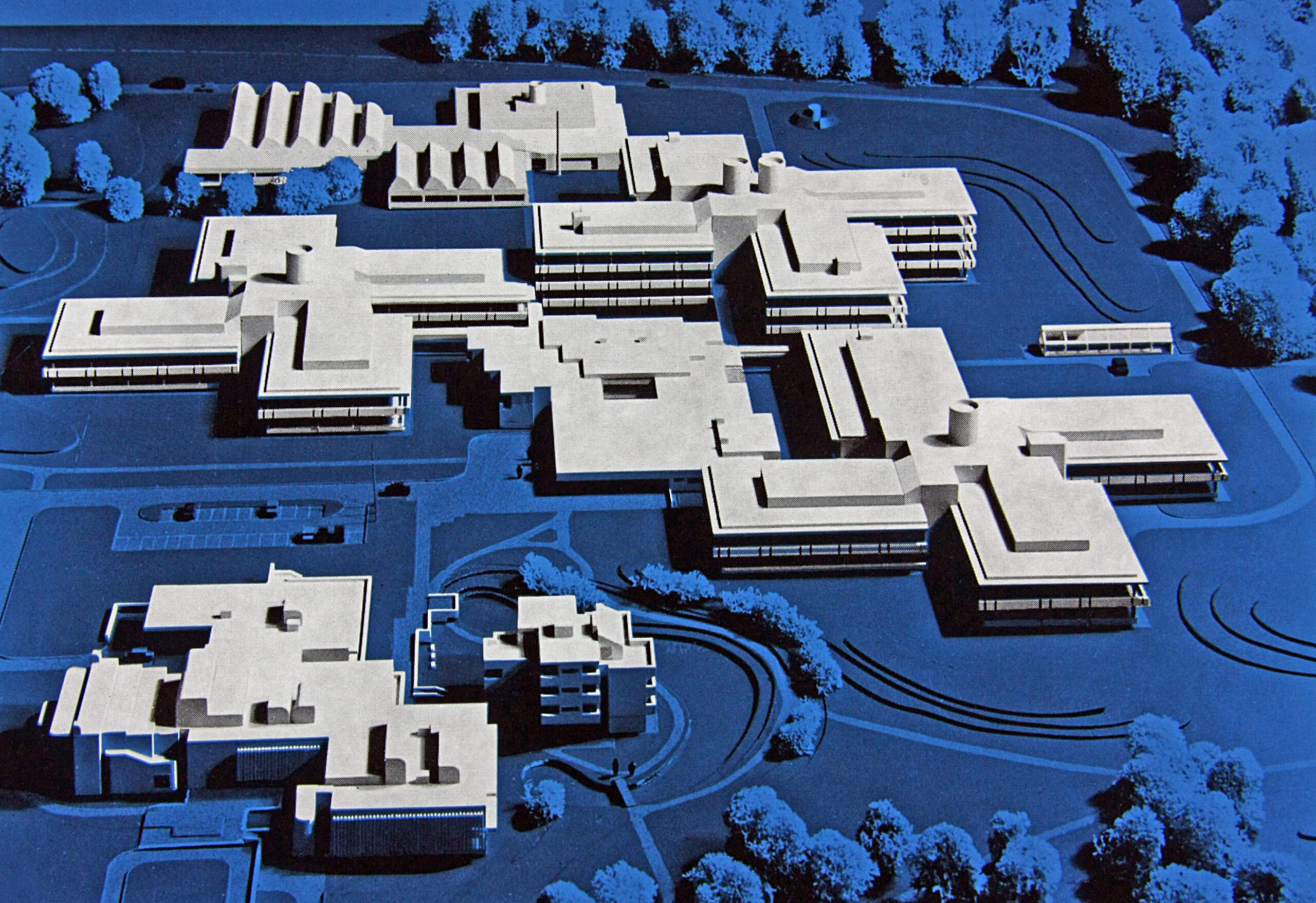

Much remained to be done before the new institute could begin its work. To start with, the buildings had to be planned. This task was taken on by the Frankfurt architects Beckert & Becker in 1967, whose design prevailed in a competition against 13 other building concepts.

Their idea was a modern research campus based on American models. Corresponding to the aesthetic taste of the time, it was to be built wider rather than higher. Its star-shaped floor plan assigned separate wings to the individual departments, each with an area of around 1,200 square meters.

The common facilities such as the library, the guest house, the workshops, the canteen and two lecture halls were located in adjacent buildings.

1974

The directors of the Institute together with MPG Honorary

President Adolf Butenandt

The directors of the Institute together with MPG Honorary

President Adolf Butenandt

Standing – Erich Wünsch | Gerhard Braunitzer | Peter Hans Hofschneider | Walter Hoppe | Kurt Hannig | Klaus Kühn | Wolfram Zillig

Standing – Erich Wünsch | Gerhard Braunitzer | Peter Hans Hofschneider | Walter Hoppe | Kurt Hannig | Klaus Kühn | Wolfram Zillig

Seated – Robert Huber | Pehr Edman | Heinz Dannenberg | Adolf Butenandt | Feodor Lynen | Gerhard Ruhenstroth-Bauer

Seated – Robert Huber | Pehr Edman | Heinz Dannenberg | Adolf Butenandt | Feodor Lynen | Gerhard Ruhenstroth-Bauer

THE VISION BECOMES REALITY

THE VISION BECOMES REALITY

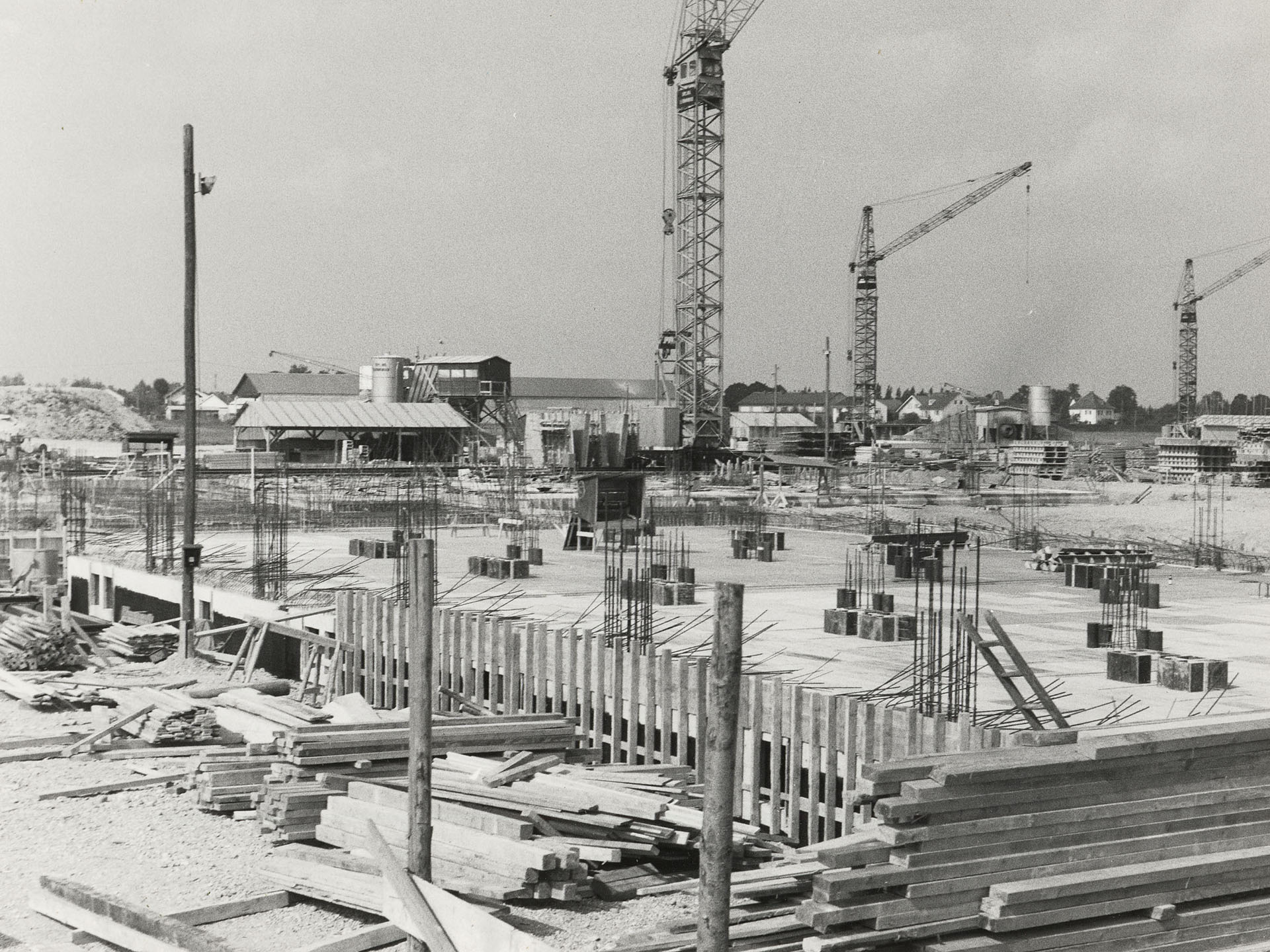

In 1969, construction work began on the green field. The research campus was literally created from nothing. However, the original schedule could not be kept. Munich was the host of the Olympic Summer Games in 1972. Therefore, in the greater Munich area, a majority of the skilled workers in the construction industry were already busy.

As a result, the Institute was not ready for occupancy in 1970 or 1971, as originally hoped. The first buildings were completed in July 1972. Four of the initially planned 11 departments began to operate — including the Enzyme Chemistry and Metabolism department headed by Nobel Prize winner Feodor Lynen. It was not until March 1973 that the construction work was fully completed.

“WELL, GO FOR IT!”

“WELL, GO FOR IT!”

The official opening ceremony of the institute took place on March 23, 1973 in the presence of numerous prominent people. MPG President Reimar Lüst and Honorary President Adolf Butenandt were present, as well as other high-ranking representatives from science and politics.

Richard Naumann, mayor of the municipality of Planegg, appealed to the scientists in a humorous speech, “Well, go for it!” The former director of the old MPI of Biochemistry, Adolf Butenandt, praised the fact that a “little Dahlem” had been created in Martinsried—an allusion to Berlin-Dahlem, where the first institutes of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society (KWG), the predecessor of the MPG, had been built at the beginning of the last century.

But different attitudes also clashed at the ceremony. When the 70-year-old Butenandt demanded of the younger scientists that they should “serve science”, he earned whistles. In the spirit of the ’68 movement, a democratic, anti-hierarchical understanding of science was on the rise.

THE DAILY ROUTINE BEGINS

THE DAILY ROUTINE BEGINS

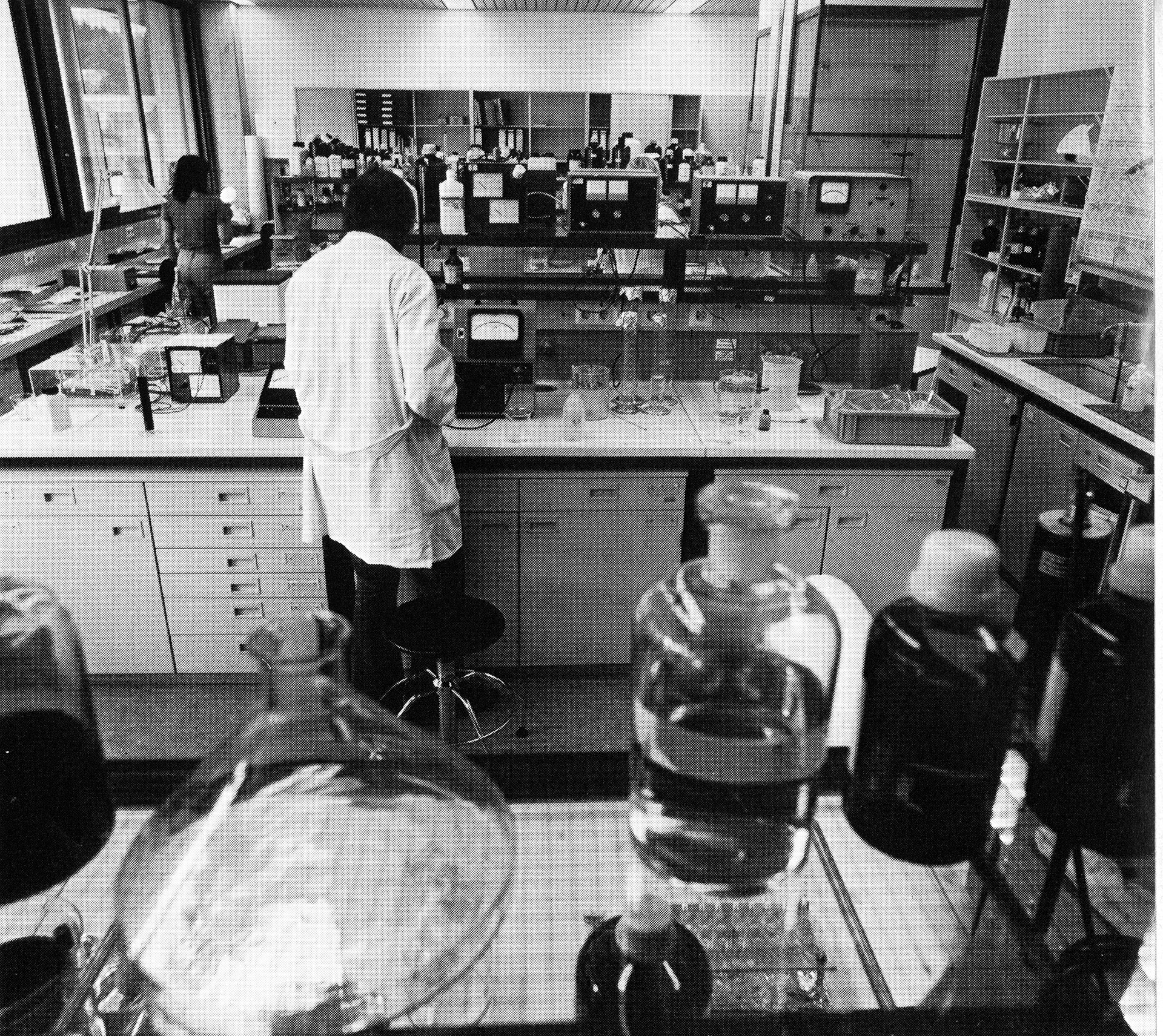

With its opening, the largest center of biochemical research in Europe began its work. By 1973, it housed 11 departments and 2 independent research groups, the number of which soon increased. At this time, nearly 400 people worked on the campus.

It now had to be seen whether the fusion of institutes achieved the desired effects in practice. “There were definitely problems at the beginning” recounted a doctoral student at the institute at that time. Although the directors had been in close contact for years, “most of the other employees didn’t know each other, they felt like strangers”.

Nevertheless, the synergies were noticeable. The central facilities proved their worth and the institute grew more and more together. Another employee wrote a few years after the opening: “The atmosphere in the new Martinsried institute was excellent, helpful and friendly staff in all departments, exemplary unbureaucratic administration.”