9 THE PRESENT OF THE PAST

THE LONG ROAD TO HISTORICAL REASSESSMENT

THE LONG ROAD TO HISTORICAL REASSESSMENT

Still to this day our scientific successes are overshadowed by the past: two of our predecessor institutes already existed during the Nazi era and played a disreputable role between 1933 and 1945.

It was not until 1983 that the darker aspects of our past were, for the first time, publicly addressed in an exhibition on the history of our predecessor institutes.

In 1997 a comprehensive scientific reassessment process started. On behalf of the Max Planck Society (MPG), an external commission of historians headed by Reinhard Rürup and Wolfgang Schieder researched the Nazi history of our predecessor, the Kaiser Wilhelm Society (KWG) and its institutes. By 2007, 17 extensive book publications had been issued. Among other things, they provided evidence that a number of institutes had been actively involved in Nazi crimes. In 2001, MPG President Hubert Markl publicly apologized to the victims and their relatives.

DISCLOSURE OF INJUSTICE

DISCLOSURE OF INJUSTICE

The work of this historical commission showed that the KWG dismissed or prematurely retired most of its Jewish employees as early as 1933, without much resistance to the dictates of the Nazi regime. The legal basis for this course of action was the “Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service” of 1933. In our predecessor institutes in Berlin and Dresden, two directors, in addition to other unnamed employees, were also dismissed for anti-semitic reasons:

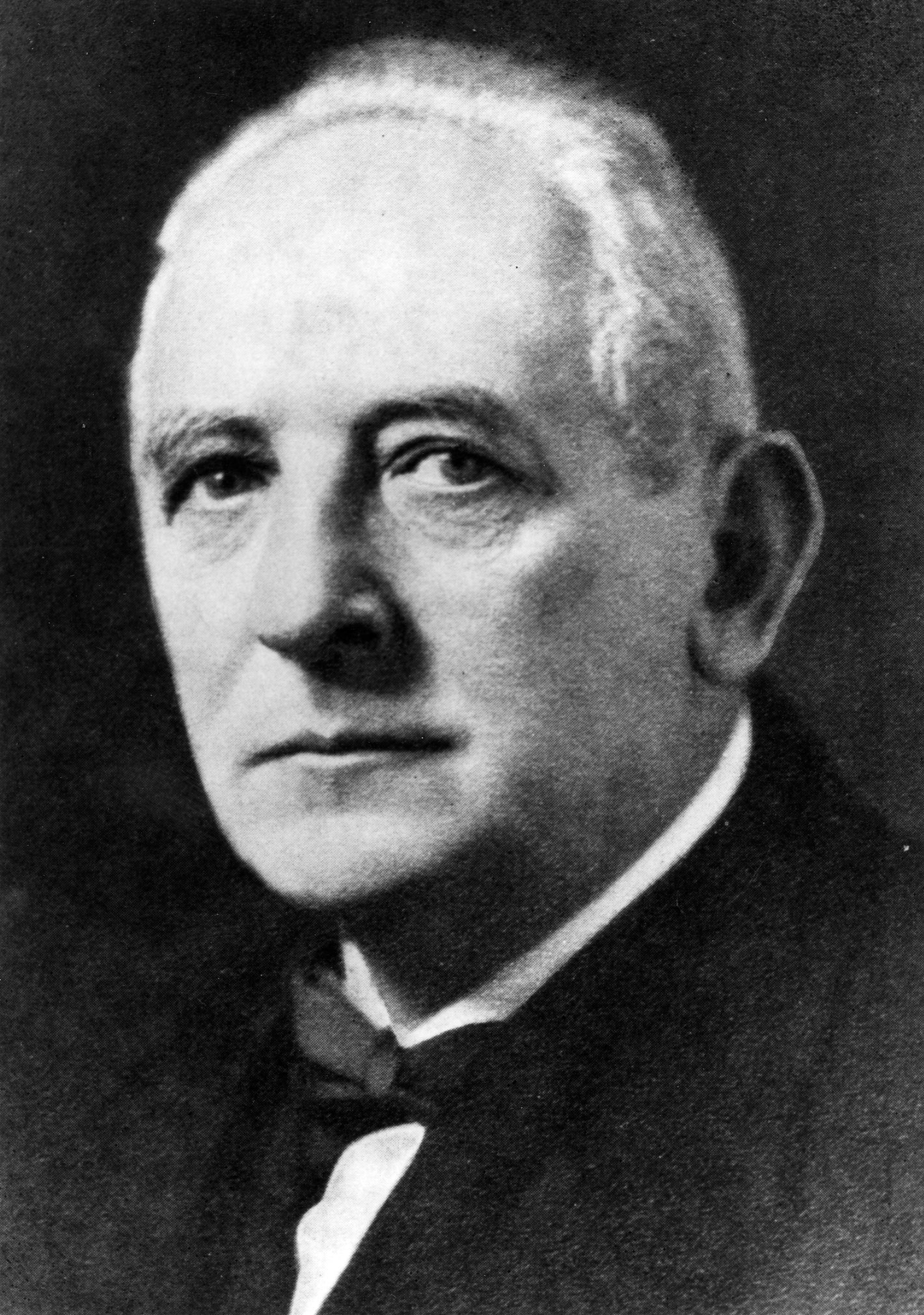

Carl Neuberg (1877–1956), head of the Kaiser Wilhem Institute (KWI) of Biochemistry in Berlin, was initially exempt from dismissal due to his service as a front-line combatant in World War I, but his forced leave followed as early as 1934. Neuberg continued his research in a private laboratory and later emigrated to the USA in 1939.

Max Bergmann (1886–1944), founding director of the KWI for Leather Research in Dresden in 1922, was dismissed in 1933 and emigrated to the USA in the same year. Like Neuberg, he continued his successful research there — finally as director of the chemical laboratory at the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research in New York.

NAMING CRIMES AS SUCH

NAMING CRIMES AS SUCH

The greatest perversion of science was the participation in human experiments. For example, a shoe test in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp was initiated by Wolfgang Grassmann, director of the KWI for Leather Research. From 1940 to 1945, concentration camp prisoners had to test shoes made of leather fiber — they had to continuously run until they were completely exhausted. Those who did not continue to run were shot.

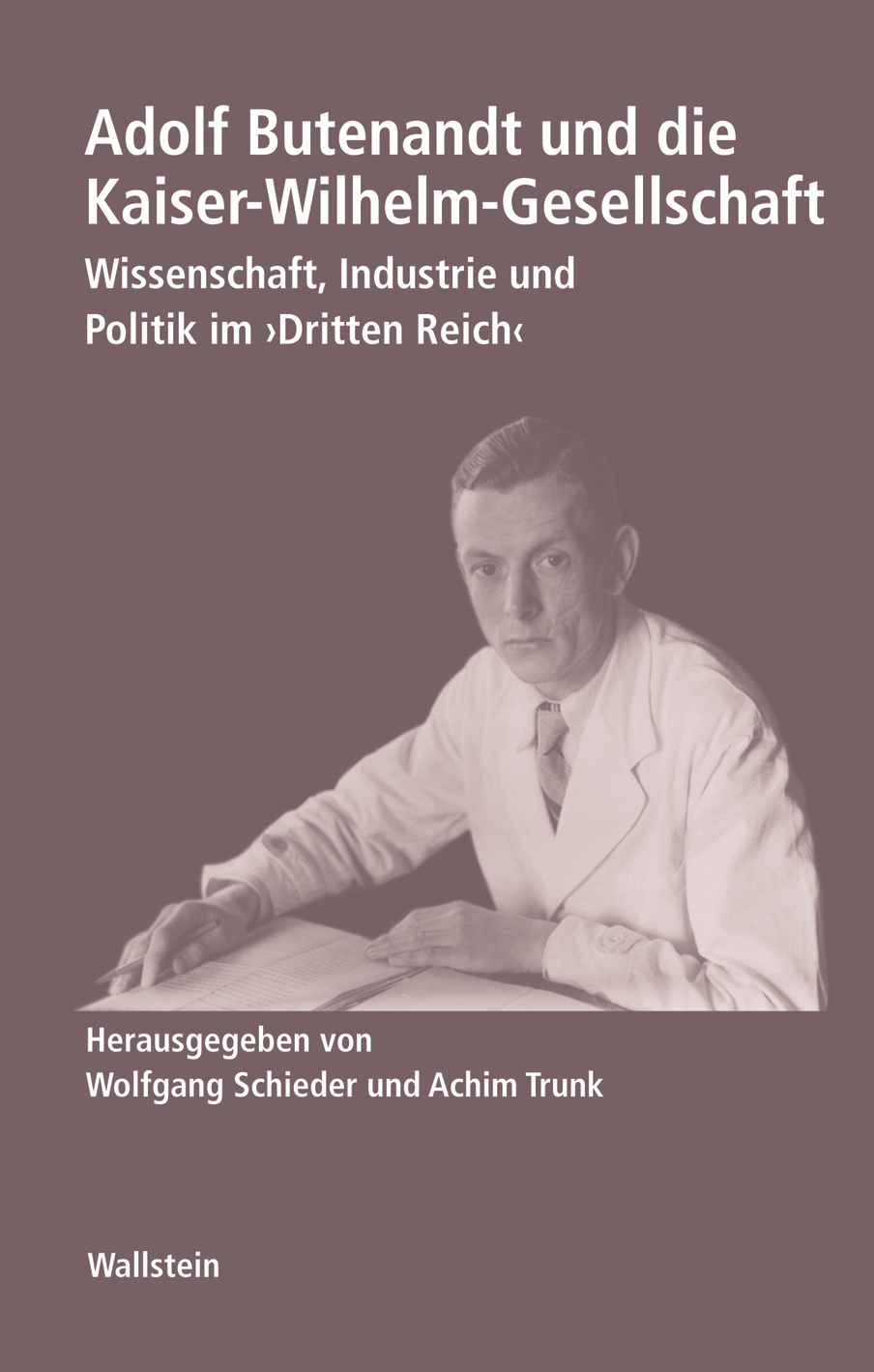

Subject of intensive research and controversy was the role Adolf Butenandt, the head of the KWI of Biochemistry, played in human experiments during World War II. Important documents from this period are missing, Butenandt kept silent about accusations. Although his involvement could not be proven, he was aware of human experiments and did not prevent them. For example, his colleague Gerhard Ruhenstroth-Bauer, one of the founding directors of our institute, conducted experiments on children in a negative pressure chamber in cooperation with the KWI for Anthropology, Human Heredity and Eugenics. Only in 2001, when Ruhenstroth-Bauer was confronted with the latest research results about that time and showed no regrets, he was banned from our institute.